Archive blog from January 2022

Customer research company Tectonic recently delivered a workshop on measuring value. Here, Dan Parry shares key insights and recommendations.

The evolution of product

At Tectonic, we believe in teaching from first principles and tend to break down ideas into the smallest elements and build from there. Although we’re all likely intimately familiar with this, let’s start from the beginning – What is a digital product?

A digital product is a tool, product, resource or service that your end-users or users interact with on a digital device or platform. The world has moved from typically dealing with biological (e.g. human) or analogue (e.g. paper) to wholly digital means of building, communicating and delivering value.

A picture that blows my mind every time is that everything in this picture now fits in your pocket.

Also, check out this video of the evolution of the desk.

End-users

In this article I typically use the term end-users to describe the main beneficiaries of a product or service. There may be multiple users of your platform from administrators, to day-to-day users. However, for clarity and brevity, I will just use the term user throughout.

Introduction to products

There are many types of digital products that we and your end user interact with on a regular basis. That timeframe may be daily e.g. an app like Instagram or only yearly e.g. an application to do your taxes.

You can also get products that your users may only end up using once which solves their problem.

Regardless of the cadence of use, your users need to get value from it. It needs to help them reach their goals, ideally in a pleasant way.

Example products:

- Mobile apps

- Desktop apps

- Games

- E-books

- Websites

- Courses

- Tutorials

- Guides

- Online content

- Downloadable content

- Etc…

Interacting with products

There are usually only a few ways that people can interact with your digital product. They may be read-only, like your favourite restaurant’s website or they may be more functional, like an app to connect foster parents together. The main difference between them is something we like to call CRUD.

CRUD stands for Create, Read, Update, Delete.

It’s important to think about your users’ needs and how they will get value from your service. CRUD covers the basic elements of most digital products.

Create: Can your users create posts, images, events?

Read: Can your -users read articles, courses, data from a dashboard?

Update: Can your users edit things they’ve posted, written, shared?

Delete: Can your users remove things they or someone else has created?

Introduction to building digital products

When thinking about creating products for your organisations, there are a few things you need to consider.

What problem am I solving?

Write one succinct sentence down as simply as you can. This makes it easier to determine if you understand the problem well enough, and if your users understand it in the same way.

Who is this a problem for?

Do you know who your ideal user is? Does everyone in your organisation agree? If not, why not?

Is this really a problem?

Have you got evidence that this problem exists for your user? Have your end users tried to solve the problem themselves in some way?

What’s the least I can do to solve the major pain point?

What is the smallest thing you can create to solve the problem for your users? Tackling the critical pain will usually have knock-on effects for them and your organisation, so you want to minimize and control these effects.

What does success look like?

How will you know if you’ve delivered value to your users and your organisation? Can you quantify this? Are your metrics of success the right metrics to track?

Creating valuable products

One of the key aspects of digital products is that you’re able to create value at scale. You can help larger numbers of people from one central place. You don’t have to travel, or even be there in person, but you do have to be human.

The people that you’re trying to help have goals, needs – and sometimes vital and time sensitive ones. So in order to help effectively, you’ll need to test your assumptions, and iterate quickly, in order to ensure you’re helping people as best as you can.

And it’s faster than ever to learn what’s working and not working with digital products. The key is to understand how your end users usually measure value in their minds.

There are four key types of value: functional, monetary, social and psychological.

Functional value: This type of value is what your product does, it's the solution a product provides to the user.

Questions to ask yourself: What are my users trying to practically accomplish? Are they trying to find the right services to aid them? The perfect song for their mood? Are they trying to apply for a loan? Does your product help them achieve this?

Monetary value: This is either where the function of the price paid is relative to an offering's perceived worth, or it can also be seen from the view of saving your users money if they directly equate their time to money.

Questions to ask yourself: What is the monetary value they equate to the outcome of using this product? Do they believe they are getting more out of it than it costs them – either in time or money?

Social value: The extent to which owning a product or engaging in a service allows the user to connect with others. This is primarily for networked products where your users may interact with each other or see each other’s status.

Questions to ask yourself: Does my user place significance on their social status within the sphere this product is in? Does my product even need peer-to-peer interaction? (It’s fine if it doesn’t).

Psychological value: The extent to which a product allows consumers to express themselves or feel better. This is one of the most important aspects, but depending on what you’re building it may be more of a focus, or in the background.

Questions to ask yourself: How does your product legitimately improve the lives of your users? How will you ensure their safety? How will you intentionally help them feel better after using the product?

User value: is the sum total of the value a person or group of people receives from your product. And just a note, your product doesn't have to score highly in all areas. E.g. Netflix has high psychological value but low social value. Airbnb has high functional value but (depending on your choice) can be low monetary value. It doesn’t mean neither is valuable to their users.

But in order to determine your value, you must speak to your users. They are the ones that determine this.They will be the primary judge of the value you and your organisation are providing. It’s up to you to understand from your users what the value is…and then adjust accordingly. E.g. if you want your users to feel more social value, then find out what being social means to them and implement that.

How do you track that value?

So once you’ve built a small version of your product and spoken to your users to determine what they expect from it, how do you measure and track that value? Well, it’s important to set measurable, quantifiable goals.

It’s important that they are quantifiable so you can determine whether you are reaching them or not. Also, quantifiable goals make it easier to defend your product within your organisation.

An example of an ambitious (but vague) goal would be to:

Help underprivileged people in London.

This is a worthwhile goal. However, it’s vague and difficult to track.

A more specific goal would be to:

Help 100 underprivileged women in the Borough of Hackney successfully apply for our service by June 2022.

And to reach those goals you need to set systems in place to try and reach them, and to pivot where necessary.

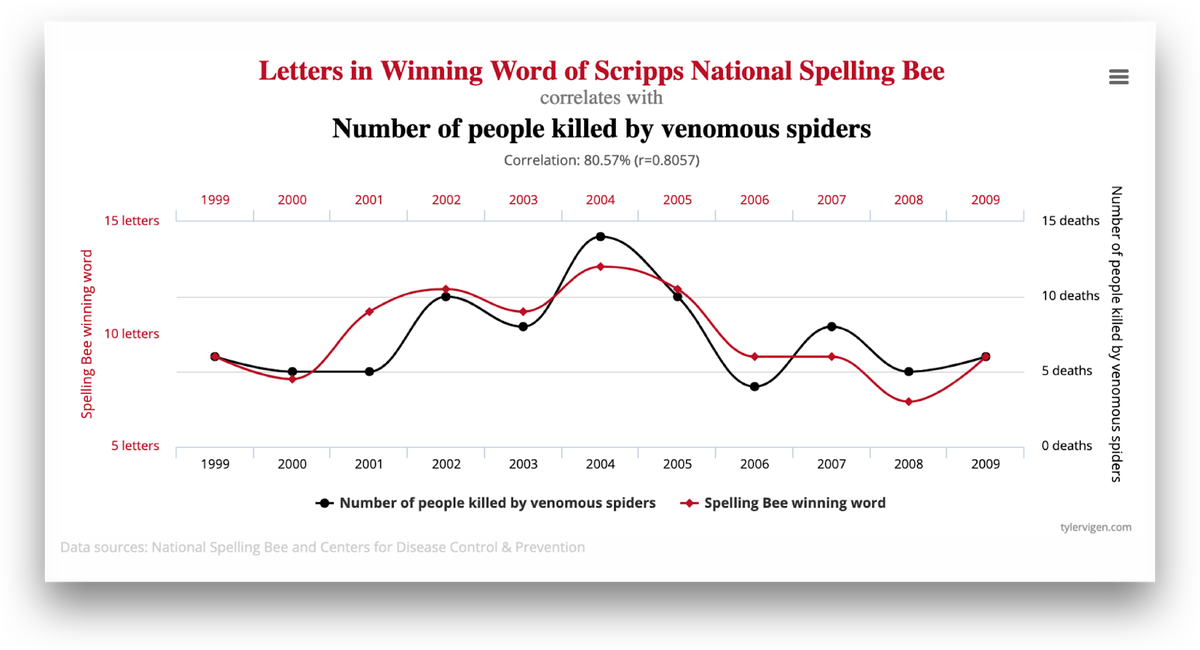

However, tracking all metrics isn’t all that useful. And can sometimes be dangerous for your organisation. You can end up making poor decisions because you’re looking for trends where there are none.

The above diagram shows the correlation between the number of words in a spelling bee and the number of people killed by venomous spiders. (This is the only reason I don’t enter spelling bees and not because of my terrible spelling and stage fright.)

Correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation.

There’s a really great site that shows you two pieces of data that look like they are connected, but are very much not. Check it out here: http://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations.

Warning: The stats can be quite morbid, but hopefully from the examples you’ll be able to tell that just because data points are similar they don’t have any direct correlation with each other.

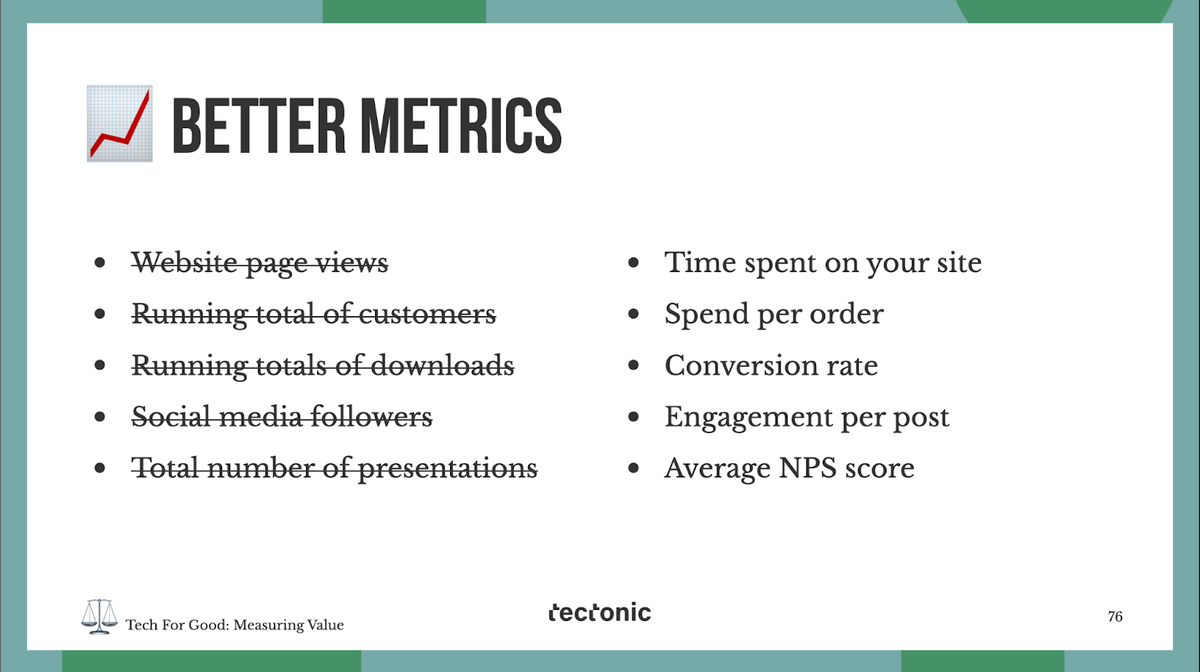

Vanity Metrics

One way to avoid this is by focusing on the right metrics. Let’s start by understanding what you shouldn’t track. Vanity metrics are metrics that seem like they would be good to track but aren’t actually meaningful for your organisation, department, product (or life).

Example vanity metrics:

- Website page views

- Running total of customers

- Running totals of downloads

- Social media followers

- Word count

Most of these numbers can’t actually go down. And as they go up, they make you feel like you are performing well, but aren’t a good measure of how your projects are actually doing.

For example the number of words in this blog post isn’t a good indicator of the quality. A writer can work to increase the word count by padding out the content with unnecessary filler – and this is the antithesis of real quantifiable value. A metric to track instead might be numbers of shares or engagement on the blog post.

Here are a few more examples:

*An NPS Score is the net promotor score and is usually a mneasuremenat of how likely someone would recommend a product or service to a customer or colleague. Read more here: https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/experience-management/customer/net-promoter-score/.

Key Value Metrics

The reason why focusing on multiple metrics may not work is because the goals may be at cross purposes with each other. A marketing department’s aim may be to get 100 leads a month, and a sales department may track the average size of a sale.

If the marketing department generates 100 low quality leads, they still reach their goal. If the sales department spends time schmoozing a few big clients to increase their average, they complete their goal.

However, the business is at cross purposes and may not be delivering value to as many people as it potentially could.

A simpler way to approach this, however, is to focus on one quantifiable metric – one, that if your organisation accomplishes it, will meaningfully provide value to your users and organisation.

Simplicity is key.

Examples

Spotify

A streaming service that gives users the ability to listen to millions of tracks for a monthly fee.

Potential vanity metrics: Number of songs on the platform, number of customers, revenue generated.

Key value metric: Repeat subscriptions

Reason: If the whole business focuses on trying to keep repeat subscriptions up, then they know they are delivering value, artists will generate more revenue, the business will make more money, customers will likely go up through word of mouth etc…

Fortnite

A free to play video game where the key transaction is in purchasing designs to make the characters look different, or dance moves to stand out.

Potential vanity metrics: Number of players, revenue generated, skins or emotes bought…

Key value metric: Hours in the game

Reason: By focusing on making the game as rewarding and social as possible, players will spend time in the game, form meaningful relationships, have fun and by extension invite other people to play, likely buy more in-game products, and generate revenue for the company.

These are very commercial products, but the point still stands. By focusing on one key value metric, you can ensure that you are delivering value to your end-users, and keep everyone in your organisation aligned to the goal.

In Summary

When building a digital product it’s important to understand the value you want to provide and the value you are providing. You can typically break them down into functional, social, monetary and psychological value. As an organisation or department, you may have assumptions about the value you provide, but it’s actually determined by your end users. So it’s important to learn from them, track your efforts, and iterate swiftly, and accordingly.

Tracking your efforts may seem daunting, but simplicity is key. What is one key value metric you can all strive for that provides value to your users and the organisation you work in? Focus on that and everything else should improve.

Tectonic

We’re a hyper targeted customer research company that helps B2B businesses and not-for-profits find their ideal end-user so that we can learn from them to help you achieve your impact goals. If you’d like to learn more, reach out to me directly at [email protected] or visit the site www.tectoniclondon.com.